My Manchester Metropolitan University page: http://www2.mmu.ac.uk/hpp/research/current-phd-students/

Please help fund my research: http://www.gofundme.com/medievalgardensandparks – just over 50% funded to date.

My Academia.edu page: http://mmu.academia.edu/SpencerGavinSmith

This week I’m looking at the wider world around Dolbadarn Castle (Latitude 53.116526; Longitude -4.114234) after spending the last three weeks in these blog posts:

2 https://medievalparksgardensanddesignedlandscapes.wordpress.com/2014/12/30/facial-recognition/

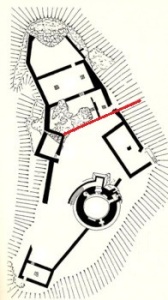

looking at the ‘male’ and ‘female’ sides of the structure and architecture. But how does this structure relate to the wider world in which it was constructed? The answer interestingly, has been staring everyone in the face since the very beginning. Llanberis as a village saw little growth in the post-medieval period until two separate factors, the Industrial Revolution and the tourist trade changed the perception of the landscape and to a greater and a lesser extent respectively the landscape itself. The former need not detain us here, but the latter is important in terms of how visitors to this part of Snowdonia interacted with their surroundings.

After the first pioneering tourists in the 1770s came the landscape painters. After the landscape painters, some of whom exhibited in places where their work was viewed by the British upper classes, came Royalty. They wanted, it seems, to see what all the fuss was about in this part of the country. Queen Victoria arrived in 1832. To honour her visit there was a Royal Victoria Hotel, a Victoria Terrace, a Pont Victoria ‘Victoria Bridge’ and a plantation of trees named ‘Coed Victoria’ – Victoria’s Trees. The hotel was constructed in the early nineteenth century to cater for the burgeoning tourist trade and was extended in late nineteenth century.

On the 1st edition Ordnance Survey map – dated 1888 – in addition to the panoply of ‘Victoria’ names there is an area to the west of the castle called ‘Parc Bach’, in English ‘Little Park’. The name ‘Parc Bach’ represents a survival of the Welsh royal landscape and provides an additional piece of evidence for the sophistication of Llywelyn and Joan’s castle.

A little, or inner park was a park which was constructed in close proximity to a high-status residence from the twelfth century onwards. A little park could serve a variety of purposes, but was principally designed to serve as a backdrop to the buildings, and could also serve as a venue for staged events or entertainments. A window in the western gable end of the Joan’s hall would allow a view into the park, and an examples of this type of arrangement are known from Woodstock (Oxfordshire) and Windsor (Berkshire).

All the evidence presented in the last four blog posts has been recovered without the use of archaeological excavation and by using evidence derived from the maps, fieldwork and the visible architecture and I hope it has provided you with food for thought. In the next blog post we’ll be on the other side of my study area in Shropshire, looking at an early seventeenth century map and what it can tell us.