My Manchester Metropolitan University page: http://www2.mmu.ac.uk/hpp/research/current-phd-students/

Please help fund my research: http://www.gofundme.com/medievalgardensandparks – just over 50% funded to date.

My Academia.edu page: http://mmu.academia.edu/SpencerGavinSmith

This week we are on the Shropshire / Flintshire border looking at Tilstock Park (Longitude 52.931698; Latitude -2.710032). The earliest date for a park at Tilstock is 1361 when it is recorded in an ‘Inquisition Post Mortem’. An Inquisition Post Mortem recorded the lands held at their deaths by tenants of the crown.

If want to know more – have a look at http://www.inquisitionspostmortem.ac.uk: “The project will publish a searchable English translation of the IPMs covering the periods 1236 to 1447 and 1485 to 1509. From 1399 to 1447 the text will be enhanced to enable sophisticated analysis and mapping of the inquisitions’ contents. The online texts will be accompanied by a wealth of commentary and interpretation to enable all potential users to exploit this source easily and effectively.”

Back to our particular Inquisition taken in 1361, which was taken on the death of Ankaretta Lestrange. Although the park is not recorded prior to 1361, it must have been in existence prior to this date for it to be included. From 1361 to the end of the century there are records of the Parkers (those officials responsible for maintaining the parks) but in this post I want to look at the ‘death’ of the park, rather than its ‘life’.

During my research I found this image which was published in Rowley, T. 1972 ‘The Shropshire Landscape’, Hodder and Stoughton, London.

(The annotations are mine on a photocopy before anyone thinks the book was defaced!)

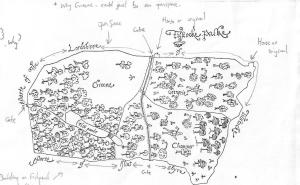

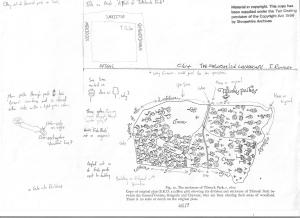

This map – produced c.1600 – shows the ‘death’ of Tilstock Park. With the trees being chopped down by men equipped with axes. Having looked at this map in the book, I wasn’t happy with the reproduction of the original as some things didn’t look quite right, and it said in the book there there was no north marked on it.

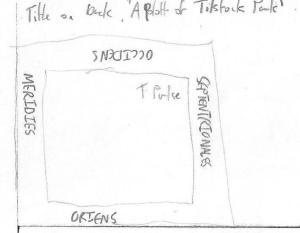

I thought I’d use my copy as it shows my ‘workings out’, and gives some idea of how I look for clues, both in maps and in the landscape. Firstly, the original map does have north marked on it, it just happens that it is written in Latin.

Septentrionales = North / Meridies = South / Oriens = East / Occidens = West

Another way of orientating the map would be to look at where the county of Flintshire is marked, and in this case the county of Flintshire should be to the west of the county of Shropshire. So, with the map orientated, what other clues can we glean from the map?

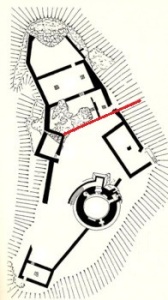

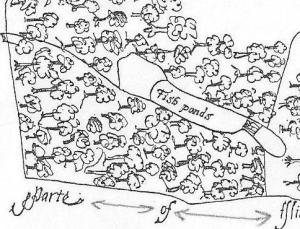

Tilstock Park in its final incarnation had two gates, one on the western side and one on the eastern side. The gate on the western side had a park lodge outside of the park on the northern side, and there was another building in the north western corner of the park. On the southern side of the park was a water gate which allowed the flow of water to be controlled into a series of fish ponds on the south eastern side.

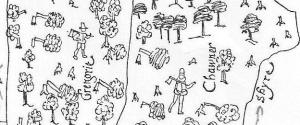

Rowley thought that the park was divided into three – and in the ownership of Greene, Chawner and Gregorie. However, although Chawner and Gregorie appear to be depicted on the map, with axes over their shoulder, there is no sign of Greene. It would appear that in this case Greene refers to an open space, something we would expect to find in a medieval park.

Chawner and Gregorie are probably felling the trees in Tilstock Park in order to see them off and make some money as they change the use of the park from something which would have derived its income from a variety of sources, for example from the deer and other animals kept in the park, from the fish in the ponds and from the sale of wood. The park would now become an open space used as farmland, in this case pasture for sheep or cows.

Armed with the knowledge the original map was kept in the Shropshire Archives in Shrewsbury, I went to see why it hadn’t been reproduced in the book and why Rowley had made a copy. When I saw the original, I quickly understood why. The map was in several shades of green with black ink illustrations on top. This meant it was very difficult to read, and even more difficult to photograph.

So, what does Tilstock Park look like today?

The most obvious feature visible in the park from the air is the site of the former fish ponds.

The boundaries of the park are also clearly visible, and next week we’ll look inside the park in greater detail to see what else can be identified in the archaeological record.