Apologies for the lack of activity. I have been chronically unwell (again). That, coupled with the shear volume of material I had collected, and unfortunately also curated, meant I felt I had nothing constructive to offer by the way of a blog post. Finally however, my last operation – hopefully for a while at least – will be on the 22nd of April 2016, so I expect to be able to write happily unencumbered by the usual ever growing rock army of kidney stones.

In among all this internal excitement I have also moved house. We (my wife and our three cats) now live in the flat which used to belong to my paternal grandparents. Built in the 1970s, it is light, bright and airy and most importantly my desk is now by a big window rather than tucked away in the far corner of the last place we lived.

As part of the moving in process I decided I would re-establish the container garden my grandfather maintained, and pots and soil in hand I planted up some heather and lavender and replanted my wife’s strawberry plant. As I stood and admired my handy work from the kitchen window, arm deep in washing up suds, I decided I would work on the material for my PhD chapter on gardens. It is by far the weakest chapter in terms of content and structure, but the strongest in terms of the new discoveries I have made during the research process. Unfortunately, many of these ideas have gone straight into the lecturing notes and Power Point presentations, rather than into the chapter as they should have.

Last summer I was fortunate enough to be one of two archaeologists working on an archaeological excavation in Rhuddlan (Latitude 53.288595; Longitude -3.463749). I’ve blogged about Rhuddlan previously, see:

https://medievalparksgardensanddesignedlandscapes.wordpress.com/2013/08/11/our-dark-garden/

and

for some context to the area of North Wales I’m talking about.

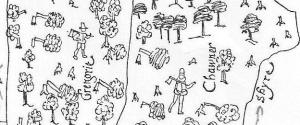

The excavation was undertaken for a client who had planning permission to build a new house within a medieval burgage plot directly opposite the north-west corner of the Edwardian castle [A burgage was a town rental property owned by a king or lord. The burgage usually, and distinctly, consisted of a house on a long and narrow plot of land with a narrow street frontage]. A preceding archaeological evaluation, which examined only a small percentage of the total area of the site found medieval and post-medieval pottery and hints of some kind of ditch system within the plot.

Documentary research established that the front of the burgage plot was now lost under part of a row of nineteenth century cottages, but the rear of the plot, as far as all the evidence indicated had been unencumbered by buildings and appeared to have always served as a garden in one form or another. My fellow archaeologist and I employed the services of a mechanical excavator to remove the considerable overburden dumped on the plot from the building of both the cottages at the front of the plot but also from the construction of another row of nineteenth century cottages to the western side of the plot.

The archaeological excavation of the medieval deposits revealed that the rear of the plot had not been occupied by a property, but had served as open space within which over the following centuries a series of pits and ditches had been dug, some of which had animal bone within them. However it was something far more ephemeral which was uncovered that I was more excited about for my PhD research.

The natural ground surface (that is the surface into which we find cut the earliest archaeological deposits on any site) was on one part of the site imprinted with the ends of tree roots. This was where a tree had established itself within the soil higher up than the natural and had then tried to extend its tree roots through the natural. In this case, the natural was a very hard and impermeable clay, meaning the tree roots left ‘dents’ as it tried to force its way into the ground.

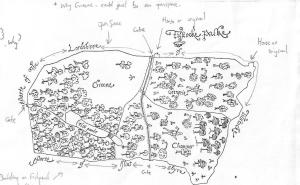

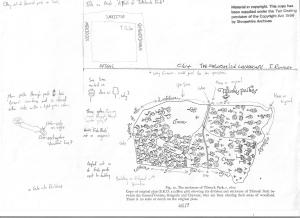

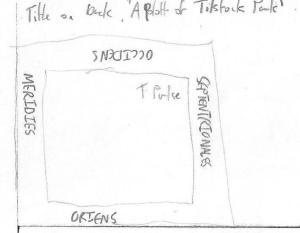

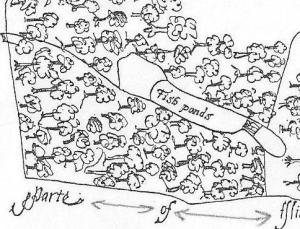

Why are tree root indentations exciting? The Edwardian castle garden was only 80 metres (262 feet) away and planted on identical geology. Although all above ground evidence, except for the well within the garden has disappeared, the excavations reveal the kind of archaeological evidence we should expect if an excavation on the site of the Edwardian Castle garden was undertaken. And I haven’t given up on the idea that I could be the person to lead and carry out that excavation.

FURTHER INFORMATION:

My Manchester Metropolitan University page – which describes the aims and objectives of my PhD research:

http://www2.mmu.ac.uk/hpp/research/current-phd-students/

You can also help fund my research – which has reached its original funding target. However if you like what you read, then you can still donate.

http://www.gofundme.com/medievalgardensandparks

My Academia.edu page – where you can download my published research:

http://mmu.academia.edu/SpencerGavinSmith