This week saw the announcement of the death of Philip Davis. It will pass unremarked upon by the national press, and I expect nearly all the readers of this blog will not have heard the name.

But you really should have heard of him, and I hope steps can and will be taken to preserve his legacy.

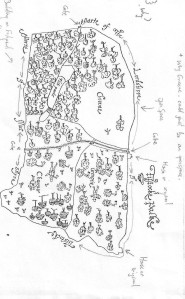

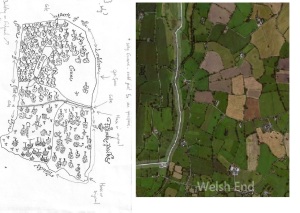

Those of us who grew up before the internet age and the widespread use of computers had to learn a different set of practical skills than today. When I began my training as a surveyor, much of our time was spent either in the drawing office, working on drafting skills on a drawing board with pencil and set squares, or outside in the field gaining practical experience in collecting dimensions using chains and tapes.

A Surveyor’s Chain

A Surveyor’s Chain

Although we had pocket calculators, our lecturer used a slide rule (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slide_rule) for calculations, and would produce an answer far quicker than us and our frenetic button manipulation. Our time on the computers was an hour a week, using a very simple drawing programme to join (literally and figuratively) the dots on the screen.

When I moved disciplines from surveying into archaeology, and went to Bournemouth University, I revelled in the Copac computer terminals. I could search for journals and books without having to flick through a paper catalogue and I would begin to remember where certain items were to be found on the shelves.

There was also the internet. In the mid 1990s it was not the academic resource we know today, but one of the earliest websites I used regularly was ‘The Castles of Wales’ (http://www.castlewales.com). As an expat living over the border in England, here I could explore the archaeology and history of Wales and begin to formulate ideas about the direction I wanted my academic research to take.

Another early site was the English Heritage Geophysical Survey Database, which was created in 1995 to provide a publicly accessible index of all the geophysical surveys of archaeological sites undertaken by them. The website itself no longer exists, but you can explore elements of it here, archived by the Archaeology Data Service: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/ehgsdb_eh_2011/

Which leads us to Philip Davis.

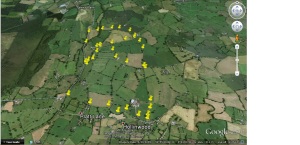

In the 1990s Philip created and curated ‘Gatehouse’, a website he described as The comprehensive online gazetteer and bibliography of the medieval castles, fortifications and palaces of England, Wales, the Channel Isles and the Isle of Man.

It is a phenomenal piece of research.

http://www.gatehouse-gazetteer.info/home.html

By his own admission, Philip was an amateur with no academic qualifications in his chosen field of study, but Gatehouse was, and is, the first port of call for any one interested in researching the history and archaeology of castles. Its breadth and depth of material is quite astonishing, with every castle having an entry, and every entry containing a considerable amount of detail. Drawing on national and regional databases, to which he added additional information, it is the kind of resource I could only dream of twenty years ago. Somehow, if steps have not been taken already to do so, this website should be curated and kept accessible for all to use.

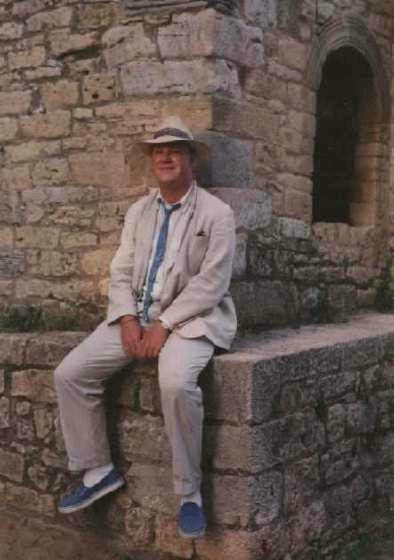

I last saw Philip in June. He and I attended a study weekend in Oxford on Medieval and Tudor Gardens. We sat and talked in a courtyard next to the lecture theatre, where we each complimented the other’s work and happily passed the time.

I will miss him.